Street Fighter 4 Character Detection

I like watching Street Fighter 4 game replays on YouTube. In fact that’s probably my biggest time sink. So one day I was watching a piece of commentary by Capcom (creators of the game) on a match, and the commentators essentially said, “I wish there was a way to measure the distances between the two characters in the game.” That made me pause for a while. I know computer vision. And I love Street Fighter. So why not try some SF4 character detection?

Task

Given a frame of a SF4 game reply, locate both characters in the frame.

Motivation

In the Street Fighter game series, there is a situation known as the neutral game, where neither player has an advantage over the other and they’re both trying to gain positional or some strategic advantage through a combination of pokes (e.g., standing jab, fireballs) and movement. To a lay observer, it would seem like the two characters are just doing the tango, walking back and forth and never getting close to one another. But at a competitive level, there are very specific distances that the players are trying to maintain, where they can gain an upper hand. If we can detect the two characters in the game, we can easily calculate these distances and track how the two characters are spaced apart within the game and even across multiple games.

Challenges

This task may seem trivial at first glance, but there are several challenges in doing computer vision here that are unique to Street Fighter.

- Rapidly changing poses. Since characters are not bound by the laws of physics, they can quickly change poses between consecutive frames.

- High variance in body poses. Unlike real world situations such as pedestrian detection, characters in SF4 have a wide range of fighting poses that are not easy to generalize from a small sample size.

- Variance in color. You would think that a character with a certain costume would have the same color throughout the match, but in SF4, several moves will cause any character’s color to change - typically to bright yellow or white, for a brief moment.

Rapidly changing poses. This is Akuma’s standing position to crouching hard kick. Notice that the character’s pose changes instantaneously between the second and third frames.

High variance in poses. SF4 characters have a wide range of poses that are not easily generalized from a small sample.

High variance in poses. SF4 characters have a wide range of poses that are not easily generalized from a small sample.

Top row from left to right - demon flip to punch, landing after an air fireball, hurrican kick, standing hard kick, neutral position.

Bottom row from left to right - forward jump, getting hit from the air, getting swept, crouching light kick.

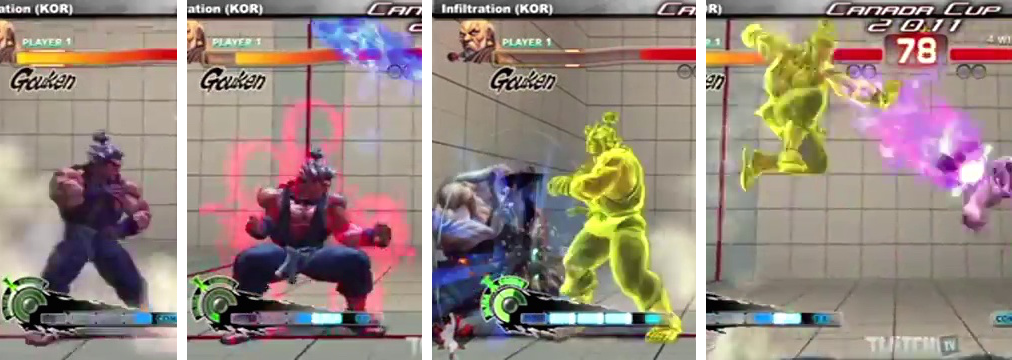

Variance in color. From left to right - neutral position, just before releasing red fireball, focus-attack dash cancel, EX air fireball

Variance in color. From left to right - neutral position, just before releasing red fireball, focus-attack dash cancel, EX air fireball

Training data

I labeled 75 frames with the x-y coordinates of Akuma’s sternum. The sternum was chosen because it’s somewhere between the character’s head and physical center of gravity - too close to the head and the window will include too much empty space above the head, too close to the center of gravity and the window will miss out most of the head.

From these 75 x-y coordinates, I had 75 positive windows and a number of negative windows several orders of magnitude more than 75. These negative examples were some threshold distance away from the positive examples, i.e. negative and positive examples did not overlap in the image.

While the general consensus in machine learning is that more data trumps clever algorithms, I intentionally limited my training set size to see how far I can go algorithmically.

Methodology

As a baseline, I’ve gone with good ol’ HOG/SVM (Histogram of Gradients/Support Vector Machines). This combination is one of the best performing detectors of pedestrians. My hope was that since they work on pedestrians, they should do reasonably well on SF4 character detection. I was slightly skeptical though, due to the unique challenges of the task as I mentioned above.

The detection procedure is fairly standard. For any given frame, we run a sliding window over the frame and get a bunch of positive predictions from the classifier (and if there’s no positive prediction we get the window closest to the decision boundary, since we know that the character is always present in every frame). We reduce this bunch using non-maximal suppression.

Results

In the following video, the detector was only trained on and is only predicting Akuma (the angry guy with the upward-pointing ponytail). The results are, in technical terms, pretty crappy. The detector often makes incorrect predictions, sometimes labeling either Gouken, or a fireball, or just a dust cloud as Akuma. This usually occurs at challenging frames where the two characters are in close proximity, which messes up the gradients in the sliding window, or where Akuma is partially occluded, e.g., when he’s lying behind the super bar.

Discussion

There’s a ton of directions that I can take this project. One obvious one would be to label more frames. But that’s such a slippery slope that I’ll probably end up labeling all the frames in this replay if I take this path. That would be the most pointless project ever.

Another possibility that I’ve already explored is active learning. Instead of blindly labeling data, you start off with a trained classifier and you perform classification on some unlabeled frames. Then you use a metric to choose which of these would give you the most information if they get labeled. You label the best frames, retrain the classifier and repeat. Unfortunately, because we are choosing among tens of frames and each frame has hundreds of sliding windows, this metric took too long to compute, making active learning an inviable method for an interactive labeling procedure.

What I’m pretty interested in trying out is some kind of unsupervised feature learning, either using something simple like K-means or a more exotic learner like matching pursuit-style dictionary learning. I’m thinking that if we learn features from the data instead of using a fixed feature extractor like HoG, we can find more descriptive features that’ll allow us to separate Akuma from Gouken.

Finally, I could try to tune the classifier by breaking my labeled dataset into training/tuning set. But the dataset is already so small at 75 examples that I’ll probably run into overfitting problems, or the tuning set would be so small that the scores it provide wouldn’t reflect the classifier’s true error. Still, it might be worth a shot.

Choices, choices.

References

Code for this project is available on Github.